Greece's Journey from 'Brain Drain' to 'Brain Re-Gain'

Greece's efforts to lure back young professionals lost during the financial crisis highlight changing perceptions of Southern Europe's political and economic fortunes

‘Brain drain’: a familiar term often used to describe the exodus of highly-skilled young professionals as they seek opportunities in more promising pastures. For those places unfortunate enough to experience it, a ‘brain drain’ accelerates a spiral of decline - setting in motion a political, social and economic multiplier effect that is notoriously difficult to reverse.

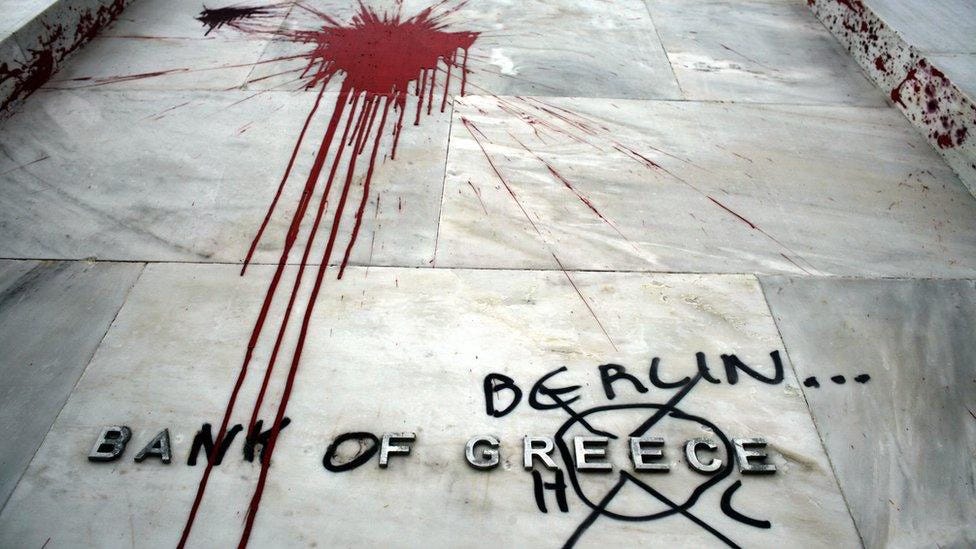

Greece found itself at this precipice during the Debt Crisis of 2010, and the subsequent years that followed. Faced with mass unemployment, a bureaucratic and archaic state, crippling austerity and increasing taxes, Greece’s educated and entrepreneurial youth started to look for a way out. For those fortunate enough to do so, joining the exodus of emigration seemed like the best possible strategy for the future.

The Schengen area – spanning the schism between the economic dominance of Germany and other Northern European countries and the perceived decline and dependence of Southern Europe – aided the emigration of young professionals and accelerated Greece’s powerful brain drain.

Many Greeks left for opportunities in Germany, Denmark, France and the Netherlands, but also to the United Kingdom (despite the latter’s subsequent exit from the European Union). During this period, many returned to their homeland only for holidays during which they could exercise their greater earning power from abroad.

At the same time, the governments of countries on the receiving end of this highly-skilled migration demanded economic re-structuring and crushing debt repayments from Greece. Other Southern European countries were not immune, with the derogatory acronym ‘PIGS’ (Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain) acting as a placeholder for a widespread perception of poor financial management, weak governance and corruption.

Now, fast forward to 2025. The economic, social and (geo)political picture has changed dramatically.

After Greece emerged from its final bailout scheme in 2018 and benefitted from the international perception of a competent handling of the COVID-19 pandemic under the new Mitsotakis government, the country seemed to have turned a corner. Digitising government functions became a top priority, whilst international tourist arrivals reached record highs. Greece was trendy again – perceived as being ‘on the up’. In turn, economic growth soared and youth unemployment was driven down to lows not seen since 2008.

Greece was suddenly characterised as Europe’s new “growth tiger” (Financial Times) and a “European success story” (The Economist). It was even selected as the top-performing economy of the year in 2023 by The Economist, with fellow Southern European laggard Spain earning the title in 2024 thanks to the highest economic growth of any major developed economy. Meanwhile, the UK, France and Germany continue to struggle with stagnating figures.

These shifting fortunes came into even sharper focus when France’s bond yields surpassed those of Greece in late 2024 – something that was unthinkable in the early 2010s. The era of sneering at the ‘PIGS’ is well and truly behind us.

All of this means Greece is now in a strong position to begin the work of reversing its brain drain, which is already bearing fruit.

As

highlighted last week on Substack, statistics show that 2023 became the first year in which Greece reversed its brain drain, after haemorrhaging young professionals since 2009. Specifically, 47.2k Greeks returned to Greece, surpassing the 32.8k who emigrated to other countries.The Greek government is officially supporting the movement of Greek professionals back to Greece through its ‘Rebrain’ programme. Here in the UK, the Greek Embassy has organised three annual ‘Rebrain Greece’ events to promote incentives for Greek professionals to return – the latest of which took place just last week at Novotel West London.

The event was attended by Ministers and the Ambassador of Greece to the UK, Yannis Tsaousis, demonstrating the importance attached to such events. Also at the event were over 1,300 Greeks and 26 companies including JP Morgan, Vodafone, Alpha Bank, PWC, EY and many more looking to recruit Greek talent.

The ‘Rebrain’ scheme also includes incentives, such as 50% income tax cuts for seven years post-return with competitive pay and career prospects.

It remains too early to say if this strategy will result in increasing numbers of Greeks returning to work in their home economy. However, it is certain that the spiral of decline that once seemed unstoppable is beginning to reverse. With increasing economic growth, a more authoritative geopolitical voice and increasing employment opportunities, Greece is in a strong position to persuade professionals from stalling economies in Northern Europe to return.

This latest ‘Rebrain Greece’ event in London only contributes further to these wider shifts in the European political and economic hierarchy. An unassuming hotel conference hall in Hammersmith is, therefore, much more symbolic than you might think.